-

-

-

-

.

Jason Flores-Williams:

Road to La Libertad

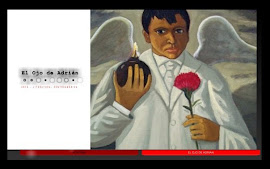

Mayra Barraza

SAL, 1966

Out of nowhere a few weeks ago, appeared a “writer from New York” working on a piece about art in El Salvador. We connected through emails and arranged to meet at the legendary bar “La Luna” with the rest of the La Fábri-K artists collective. Strong and tall, shaved head, pierced lobe, tattooed biceps and all, he was almost kidnapped by a couple of prostitutes looking for an easy dinner. Managed to crawl himself out of that one and walked in through the sounds of a furious rock session to our table, where we all dealt a quick platter of questions and answers on the role of art in El Salvador today.

Jason Flores-Williams -the brilliant writer, activist and lawyer, author of the fast and furious novel “The last stand of Mr. America”- revealed to us in an ongoing conversation for the many days that followed this strange cocktail his persona is made out to be: full of outright rebelliousness, almost childish courage and the immense open wound of a warrior.

Time flew by as he visited La Fábri-K and we took the road to La Libertad headed for the beautiful beaches of Las Flores and El Tunco, and for more than just a few days roller coasted through downtown San Salvador, Monseñor Romero´s tomb, my own “Republic of death” show, the newly reopened National theatre with Ministers of Culture included, and the ultimate cheesy gay hangout strip bar.

On the final road trip to Antigua Guatemala we snapped open a recorder and took a few shots at immortality. These here are his thoughts on death, freedom and writing.

Just a few hours later, Jason turned away and disappeared into a dark cloud. Nobody knows where he went, not even himself. I only hope he survives loneliness for I have proudly to say, he has one amiga in El Salvador waiting for that next Jason Chela.

Jason Flores-Williams: Chela? what does that mean? He’s saying: do you like my Chela, is he fucking with me? Like saying “¿qué quieres?”

Mayra Barraza: Chela in El Salvador means beer, but in México it might be a whole different story. Wait a second… Ok. This is going to be a very loose interview. More like, dropping things on the table, and then you say what you think about them. Is that good?

JFW: I think that’s a stupid interview, but go ahead. (laughs)

MB: You think everything is stupid.

JFW: No, I don’t think everything is stupid, why don’t you do your research first instead of asking me pointless questions. Go ahead.

MB: Listen, I’ve done my research. So I can ask you then why would you choose to work on death penalty cases in New Orleans? What do you think about the death penalty?

JFW: I’m against the death penalty. The thing was, I’m in New York after Katrina, a lot of people in the literary scene there talking about how New Orleans was abandoned by the U.S government. So I decided to stake it out, maybe it’s more of an ego thing to think that I can change more than I can actually change, but I also think if people are going to talk about something they should do it. So mostly I felt that if I had this ability to go down and be a small part of something in New Orleans then I should go, instead of sitting around in New York and going to parties and talking about it at night and then going back to my nice apartment. So I went down to New Orleans, luckily I was able to work with some incredible people. Death penalty work is very difficult. My first case was a guy who raped and killed a four year old on his sister’s grave, and spent the first three weeks reading about how her four year old vagina was torn out and her anus ripped to shreds. It will make you question your beliefs. Say, what the fuck am I doing fighting for this guy? But at the same time I read about him, how from the age of five till ten years old he was chained in his backyard and raped and fed dog food. So, it came down to… how the U.S. government abandons people. All these things put together, I felt like I should go down to New Orleans.

MB: Dying, killing and the death penalty. What do you think about dying for one’s country?

JFW: Well. There are different situations. Most of the time that people die for their country it’s stupid. As an American, if somebody thinks they are dying for my freedom by going to Iraq right now and dying in Baghdad, they’re not dying for my freedom. That’s just patriotic bullshit they’re buying into. We shouldn’t even be over there. Now, on the other hand, you have World War II, where you have Hitler who’s invading countries, setting up the holocaust, eventually threatening all of Europe, imposing this idiotic Third Reich, then there’s a moral imperative to go and fight. There are times when dying for your country, when your country is being attacked, is something you have to do. Like in Vietnam, which is very similar to the situation in Iraq I believe, that was just some political trick that got an entire generation killed.

MB: What about for example, insurgent or guerrilla movements?

JFW: I’m for that. I think it’s sad but when you have poor people who have no chance, and no hopes and no lives, and they are suffering, and their rights are being stepped on, they are not being treated like human beings, so what other options do they have? They get together and they march down the street, with the local mayor, the “alcalde”, a couple of them get shot, or throw the union organizers in jail, there are no other alternatives but to organize. I can’t imagine it can be very much fun to have to arm yourself and shoot the people, the police that are holding you back, kneeling you down. But I think, when you have the back against the wall, and there are whole sections of the world whose backs are against the wall, and if what they’re fighting for is dignity, if what they’re fighting for is right, then I think that’s beautiful and it’s something that you have to do. And there are other situations where poor people get trapped into bullshit ideology, dogmatic political beliefs, you know, the right or the left, where it’s just not going to come out that good either way, then there’s more questions about that… but, like the Sandinistas, it seems to me like they had the right idea about their fighting for freedom or democracy and human dignity. Same as during the Spanish civil war, out of Barcelona and Catalonia. Those kinds of things, it’s sad that they have to happen, but it’s also beautiful when they do happen, when people stand up and fight for their freedom. And I respect the American Abraham Lincoln Brigade, and of course Orwell out of England who fought as well.

MB: You talk about liberty and justice, very grand ideals, and of course they are necessary, but on a more personal level, how do you deal with these things? Because it’s necessary but it’s also easy to talk about things…

JFW: Oh sure sure… the fact is that I’m coming from America, middle class America, a world of privilege, where I can travel around and look at poor people and say wow, look at that. It’s not like it’s happening the other way around. I travel from New York to look at them, to be in their world, so a lot and part of the system that enables me to have this life is also the system that keeps things the way they are, and keeps them in their life, so there’s a lot of complicity. Now, how to break out of that complicity is a truly difficult question. Overall I don’t think that you can. Maybe you can go around fighting revolutions with other people, or talk about revolution in your own country and get thrown in jail. I don’t think that’s the way to do it. The fact is what I do is I write about it, I organize protests. I got arrested several times protesting against the war in Iraq. I’m not under the illusion that any of these things really count for all that much, but for me it’s just the best I can do. That’s really about it. If you are born in America, you have a good life going, the best you can do is try to be conscious, and then put that consciousness into as much action as you can possibly manage. It’s really going to be hard to remain consistent because you are benefiting from a system that holds a lot of people down. In my personal life I try to live in accordance to my convictions.

MB: Do you think that’s possible through literature?

JFW: Oh, I think literature is one small part of it. Just because somebody goes out and writes a story about the socioeconomic in depth, that doesn’t get him of the hook. In fact, that’s almost too much too ask. There’s too much thinking that if I go to the Philippines, if I go to fuck… El Salvador or Guatemala, Central America, or whatever, or the poor parts of the United States. Say I go to New Orleans, and write about how everybody is so poor and struggling then that makes me a good person automatically. It doesn’t. I don’t get you off the hook. In fact there’s a kind of exploitation that’s going on there. I think we are penetrated enough by information, everybody understands that there is poverty out there. I think we could use a lot more people acting and doing things.

There’s really no way out of that one. Unless you are willing to sacrifice yourself and throw yourself in the gears of the machine and die or be thrown in jail for many years, then you can’t really make a difference. At the same time, I don’t walk around feeling bad about that. I’ve made the decision that I’m going to enjoy my life. We all have our limits. That’s just the way, we are born into this world, and at the end of the day you just have to do the best you can.

MB: If literature is only a small part of your action in this world, then why write?

JFW: Well, it’s only a small part of the overall plan, but the thing is I am a writer, and mostly I write because I like writing. It makes me feel like I’m connected to the world. Some of the end results of writing can be fun. You get access to things you wouldn’t normally have access to, like for example because I write about the arts I get to hang out with you guys in El Salvador. As far as novels go, I ask myself questions about why the drive to make art. I think it’s because I have something to say. The way my life shaped up, I have experienced the socioeconomic conditions in America from various sides, and I’ve kept my life out there, I’ve traveled and lived in different places. It has to do with everything I’ve just talked about: protesting and not turning away from the problems of the world.

So for me, naturally that adds up to a story. If I have some ability to tell that story, and if that story adds up to something that clicks in peoples minds and makes them think that “aaah, then I should do a little something” then it’s seems worthwhile. But all that is kind of secondary, I think the truth is that it’s how I approach the world, and I understand the world as a writer. We drive now from El Salvador to Guatemala, and I look at it and it’s not material in some way, it’s being processed as something that can eventually work its way into a story that I can tell about…

MB: In your novel “The last stand of Mr. America”, how did you go about building up that story inside of you until it became something that you wanted to tell?

JFW: For one thing, I’ve always been fascinated by hypocrisy, and in America there’s a lot of hypocrisy. Living in society is a big lie. We have these instincts and drives, but we’ve got to hold them back so we can smile and operate within the friendly or unfriendly confines of the world. We’ve got to kill a lot of the things inside of us, or at least hold them down so we can go to work everyday and be “normal”. That’s always there for me: the fact that it takes a little bit of an effort to be normal, to function in the day to day. This was around the time I was doing a lot of sexual exploration, I would go along with a couple of good pals and go to sex clubs, and I was also doing work in the PR field, to pay the bills and get through at some ridiculous place. Those two things tended to clash and I felt it was time to create it. In my own mind, the clash and the distinction where extremely clear about how in one’s life, one’s inner truth, inner instincts, are so radically different from how they’re actually lived. And how people can have these underground lives, especially when it pertains to sex, and the kind of partying they do when they’re out of sight away from their professional sides, so radically different from the public face that they show. So that just build up ´till I had to hide myself away and build up a novel about that.

And, then there’s the economic part I tell you, when you are doing art you always hope you can get money so you can be a little more free to live your own life. I think that’s a huge part of art and nobody talks about it. People make art tying to hit the lottery in some way, so they can be economically free and won’t have to do these odd jobs here and there. But if there were absolutely no money in art, I would still make art but whether it would be a novel who knows.

MB: So, you are going to Costa Rica to write your new novel? Do you have any ideas?

JFW: Yeah, well, going to see how it goes. There are things developing… I have some idea about a guy, sort of titled “after the protest”. So what do you do when you are done with protest? The first part of my life has been a protest, an actual protest out on the street and a protest against everything. And then there comes a point where that kind of protest has to end, and what do you do after the protest? How do you live your life then? But it’s going to take a while to come together.

Where are those cookies that I bought? Yeah…

San Salvador, June 1, 2008